Format String Vulnerabilities

And how printing a string led to code execution?!!

Welcome to the binary exploitation series! In the coming posts, we are going to explore concepts and tricks used in binary exploitation. I hope you’re as excited as I am!

In this post, we’re gonna dive into format string vulnerabilities. This is a kind of vulnerability that utilizes a format string function to achieve information leak, code execution, and DoS.

These vulnerabilities have become rare nowadays, as most modern compilers produce warnings when format functions are called with non-constant strings (which is the root cause of this vulnerability). But this issue is still worth understanding because the potential impact is very critical, and because it is interesting :)

What is a format string?

Format strings are strings that contain format specifiers. They are used in format functions in C and in many other programming languages.

Format specifiers in a format string are placeholders that will be replaced with a piece of data that the developer passes in.

For example, the following code snippet shows how printf() in C works. The statement will output different sentences, depending on what is contained in the variable name.

printf("Hello, my name is %s.", name);

If the variable name contains the string ”Vickie”, the printf() statement will output:

Hello, my name is Vickie.

Format functions and parameters

Besides printf(), there are a number of format functions that uses format strings to produce output. For example in C, there are printf(), fprintf(), sprintf(), snprintf(), printf_s(), fprintf_s(), sprintf_s(), snprintf_s(), and so on. Check the C docs for more info about these functions.

And in addition to %s used in the example above, there are a number of different format specifiers. Different format specifiers indicate what type of data it should be replaced with:

- %d is for signed integers in decimal,

- %u is for unsigned integer in decimal,

- %x is for unsigned integer in hex,

- and %s indicates that the data should be a pointer to a string.

According to the data format dictated by the format specifiers, format functions retrieve the data requested from the stack.

printf("A is the number %d, B is the string %s", A, &B);

The printf() function above will attempt to retrieve the value of A and the address of string B from the stack.

How format functions can be exploited

Format functions can be exploited when an attacker is given direct control over the format string fed into the function:

printf(“If the attacker can control me, you’re in trouble.”, A, B);

The vulnerability occurs when there is a mismatch between the number of format specifiers in the string and the number of function arguments (like A and B from above) provided to fill those places. If an attacker is able to supply more placeholders than there are parameters, she can use the format function to read or write the stack.

A quick note about the stack

A detailed explanation of how the stack works is beyond the scope of this blog post. However, you should be able to find plenty of information on the topic using Google.

For now, keep in mind that local variables and function arguments are stored on the stack. This means that when you declare a local variable or function argument, it will get pushed onto the stack. And when you call a function, the function will grab data from the stack as well.

Leaking program info using format functions

So what happens when an attacker provides more format specifiers than there are function arguments to fill its place? When there are two format specifiers, but only one function argument to supply value, what would printf() do?

printf("A is the number %d, reading stack data: %x", A);

printf() will still attempt to retrieve two values from the stack. But since only one of those places on the stack is occupied by an actual function argument (A), the other value would be replaced by whatever value is next on the stack. In this case, printf() will retrieve the next value on the stack and display it in hex format.

So an attacker could simply provide the string below to read large amounts of data on the stack:

printf("%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x%x");\

-> will print the next 20 items on the stack

An attacker can even directly access the ith argument on the stack by using a special case format specifier:

printf("%10$x");\

-> will print the tenth element next on the stack

This will lead to the leaking of stack data: including return addresses, local variables, and parameters to other functions. Yikes.

Reading data at any location in memory

When %s is used as the format specifier, the function will treat the data on the stack as an address to go fetch a string from. This is called pass by reference. This means that the attacker can potentially make %s read from any address, even if the data is not located on the stack.

But how do you control the address accessed by %s? You’ll need to place an address on the stack and make %s dereference that address!

And conveniently, the format string (which you fully control) is stored on the stack! So if you can plant the address on the format string and get %s to dereference it, you can essentially access data beyond the stack.

printf("\xef\xbe\xad\xde%x%x%x%s", A, B, C);

For example, the above will cause printf() to print the string located at address 0xdeadbeef. The series of %x is used to traverse the stack to the location of the format string, and the number of %x needed will vary case by case. The %s tells printf() to treat the first four bytes of your format string as a pointer to the string to be printed.

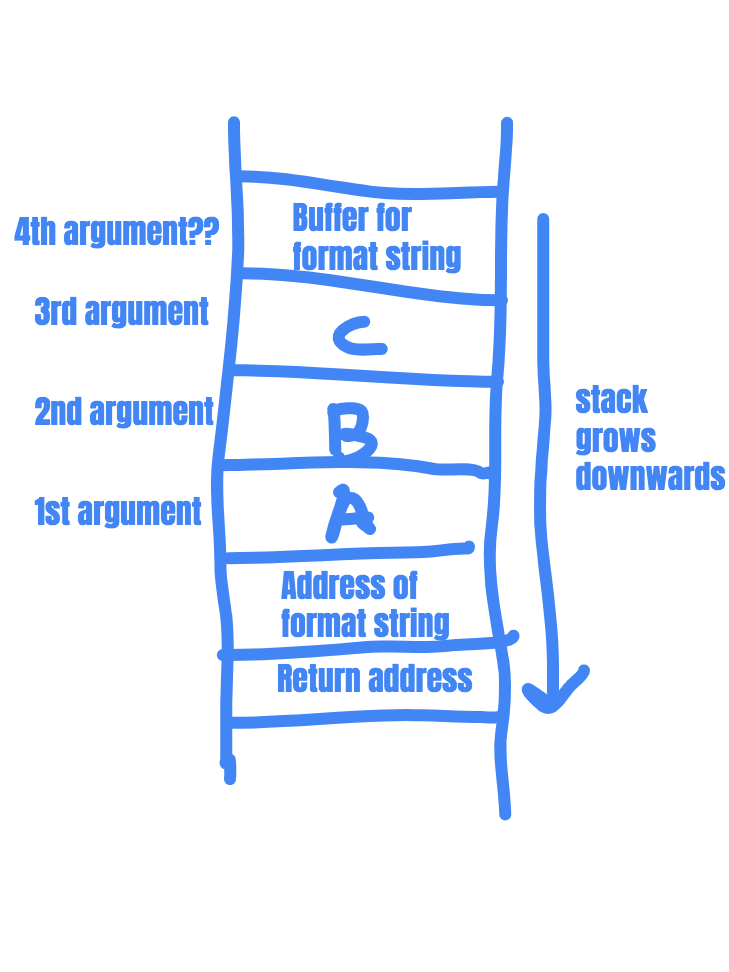

This infographic on the left shows what that stack looks like during the printf() function above.

The stack grows downwards and pushes the function arguments onto the stack one by one. printf() then goes back up the stack to retrieve the argument values.

By providing an extra %s, the attacker forces printf() to access one more value off the stack, and treat it as a 4-byte pointer to a string.

So printf() prints out the string located at 0xdeadbeef, which is the address specified by the first four bytes of our format string.

Overwriting memory at any location

In printf(), %n is a special case format specifier. Instead of being replaced by a function argument, %n will cause the number of characters written so far to be stored into the corresponding function argument.

For example, the following code will store the integer 5 into the variable num_char.

int num_char;

printf("11111%n", &num_char);

With dummy output characters and width-controlling format specifiers, the attacker can now write arbitrary integers to the location pointed to by the function argument.

The following is an example of a width-controlling format specifier, which will help attackers avoid extremely long exploit strings (And allow attackers to access arbitrary locations even if the buffer is not large enough for the number of padding characters needed).

int num_char;

printf("%10d%n", 0, &num_char);

-> will print " 0", num_char is 10

And by using length modifiers, attackers are able to control the amount of data written with fine-grain control. For example, %n will write 4 bytes into the target address, and %hn will only write 2 bytes.

printf("%10d%n", 0, &num_char); -> writes 4 bytes to &num_char

printf("%10d%hn", 0, &num_char); -> writes 2 bytes to &num_char

Using these techniques, and the trick to access any memory location mentioned in the last section, an attacker can write to arbitrary memory locations. This can allow the attacker to overwrite return addresses, function pointers, the global offset table (GOT), and the destructor table (DTORS), thereby hijacking the flow of the program and execute arbitrary code.

Crashing the program using format functions

Since function arguments for %s are passed by reference, for each %s in the format string, the function will retrieve a value from the stack, treat the value as an address, and print out the string stored at that address.

But values on the stack are not always an address. They might be integers, characters or any other kind of data. This means that if you force the function to interpret stack data as an address, the program might encounter an invalid address and crash. (This could be an address that does not exist or is located in protected address space, like kernel space.)

The exploit string would look something like this:

printf ("%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s%s");

The more %s there are in the format string, the higher the chance of encountering an invalid address.

Preventing format string attacks

While modern countermeasures to binary exploits like address randomization help make exploiting format string vulnerabilities harder, the surefire way to prevent these vulnerabilities from happening is to implement format functions properly.

When using format functions, it is important to avoid using user input directly as the format string. Instead, pass user input as function arguments that replace format specifiers.

In short, user input should go here:

printf("string: %s", USER_INPUT);

And not here:

printf(USER_INPUT, A, B);

And as an extra security measure, user input should always be sanitized and rid of dangerous characters.

Conclusion

Seemingly harmless format functions can become a major source of vulnerabilities if not used correctly. Besides C, many other programming languages have their own format functions that may or may not be immune against format string vulnerabilities. Before using them to output data, be sure to consult the documentation of those functionalities and pay special attention to the possible security implications.

Thanks for reading! Next time, we explore more techniques used to corrupt program memory, and some countermeasures developed to prevent them.